Why Digital Museums Need “Walls” Part 3: Transforming the Online Museum

Posted: October 30, 2012 Filed under: Why Digital Museums Need "Walls" 1 CommentThis is the third post in a 3-part series on reimaginging André Malraux’s Museum Without Walls and what it means for the future of digital exhibitions.

The first virtual museum was a prototype of online database museum: an image collection with label information accessed through pull down menus or search options. But access is utilitarian rather than aesthetic, informative rather than experiential.

In his book, Malraux mentions the time when paintings were mere decoration and statues were interfaces for divine communication. Art objects did not always have the aesthetic and conceptual impact they have achieved through mere presentation in a museum space. To Malraux, art becomes art when it takes on an added significance through display in an art museum. Pre-historic cave painters did not believe they were creating art. They thought that drawing a buffalo on the cave wall would lend them greater strength in the hunt. These paintings are now revered as beautiful, powerful images rather than tools.

Online museums are currently in this tool-like stage. An equally powerful transformation must occur in the digital space, one that transforms a mere “objective” image of an artwork into an object of meaning and contemplation in itself. We paint our recreations of Picassos and Monets in pixels instead of pigments but the act is essentially the same. We have been putting images of paintings and sculptures online for chiefly utilitarian, not artistic purposes.The online representation of art must become an art in itself.

Art “was always recognized as something different in kind from the world of appearances, for that quest of quality implicit in all works of art inevitably leads it rather to stylize forms than slavishly to copy them.” pg 87 — online museums should be stylized museums, not direct copies.

Bear71 embodies this new stage because the found footage has been transformed from documentation to illumination. It has become stylized. It is no longer the thing in itself but a greater thing fraught with symbolic weight.

Why Digital Museums Need “Walls” Part 2: Bear 71

Posted: September 21, 2012 Filed under: Why Digital Museums Need "Walls" | Tags: Andre Malraux, Banff National Forest, Bear 71, Jeremy Mendes, Leanne Allison, Museum Without Walls 1 CommentThis is the second post in a 3-part series on reimaginging André Malraux’s Museum Without Walls and what it means for the future of digital exhibitions.

I passed trees and train tracks, watched a cougar pad through the snow and dig its front claws into the trunk of a tree. I saw a merganser and her chicks waddle over a rocky path while, across the lake, ravens picked at the carcass of a decaying deer.

Bear 71 was elsewhere in the park, hunting for food and walking past another of the dozens of trail cameras placed throughout the Banff National Forest. But I could still hear her voice through my earphones as she narrated the story of her life. With a biting mixture of lamentation and resignation, the she took me from the moment she acquired her electric collar at age three until her tragic demise a mere eight years later.

Technology may not have advanced quite so far as to enable us to listen in on the eloquent thoughts of a Canadian grizzly, but it can provide a remarkably compelling online experience of real-world events. Bear 71, the interactive documentary by Leanne Allison and Jeremy Mendes is the future of digital storytelling and probably the future of online museums.

Allison and Mendes combined first-person (first-bear?) perspective with wildlife research data and low-res documentary footage, organizing and overlaying it upon a navigable, data-visualized representation of the Banff National Forest. Both functionally and aesthetically, the work evokes the high-tech, eternally connected culture of Web 2.0 alongside the dark, visceral awe of nature– both its beauty and its ruthlessness.

This is the Museum Without Walls of the future. It is a collection of materials accessible to anyone with an internet connection– but with a spatial navigation that enhances meaning to an extraordinary degree.

If you have 20 minutes, explore Bear 71. You won’t regret it.

In my next post, I’ll unpack further implications of Bear-71-like digital exhibitions.

Why Digital Museums Need “Walls” Part 1: André Malraux

Posted: September 17, 2012 Filed under: Museum Review, Why Digital Museums Need "Walls" | Tags: Andre Malraux, Museum Without Walls, Online Exhibition, virtual exhibition 2 CommentsThis is the first post in a 3-part series on reimaginging André Malraux’s Museum Without Walls and what it means for the future of digital exhibitions.

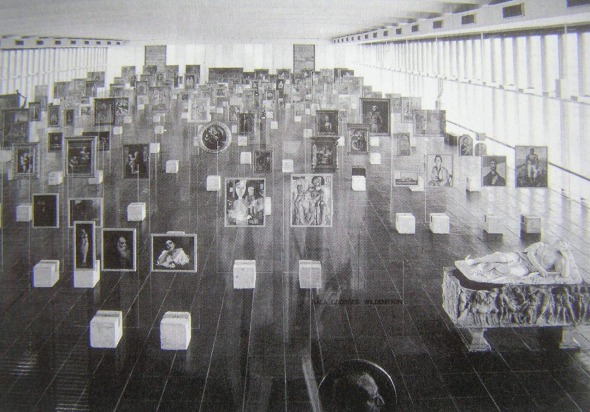

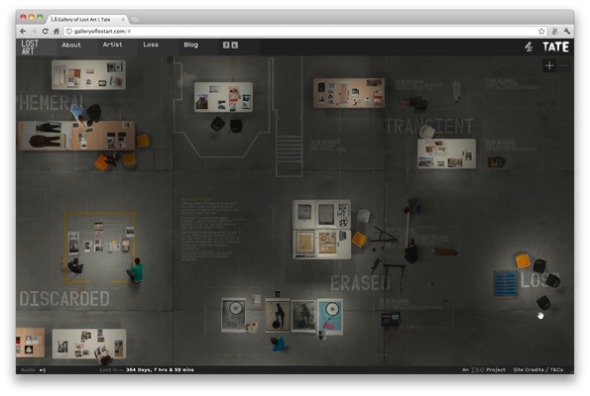

I’ve been trolling a number of online museums lately–The Louvre, Google Art Project, Gallery of Lost Art— and only just read André Malraux’s Museum Without Walls (1947). Museum writers and theorists interested in digital collections often reference Malraux and credit his conception of a a comprehensive collection of art reproductions (a museum– without walls!) as the forebear of today’s online museums and digital collections.

Malraux’s begins with the idea that, historically, taking an object out of its original context and placing it in a museum fundamentally changes the very nature of the object, changes its purpose from utilitarian to aesthetic. He writes, “the Art Museum brought about a drastic change, transforming the artist’s visions into pictures, as it transformed the gods into statues. … Though Caesar’s bust and the equestrian Charles V remain for us Caesar and Charles V, Duke Olivares has become pure Velasquez.”” (Museum Without Walls, pg 14). In this way, a table created for utilitarian purposes or a religious icon created to access the sublime are transformed into aesthetic objects, what Malraux calls style. Pre-historic cave painters did not believe they were creating art. They thought that drawing a buffalo on the cave wall would lend them greater strength in the hunt. These paintings are now revered as beautiful, powerful images rather than tools.

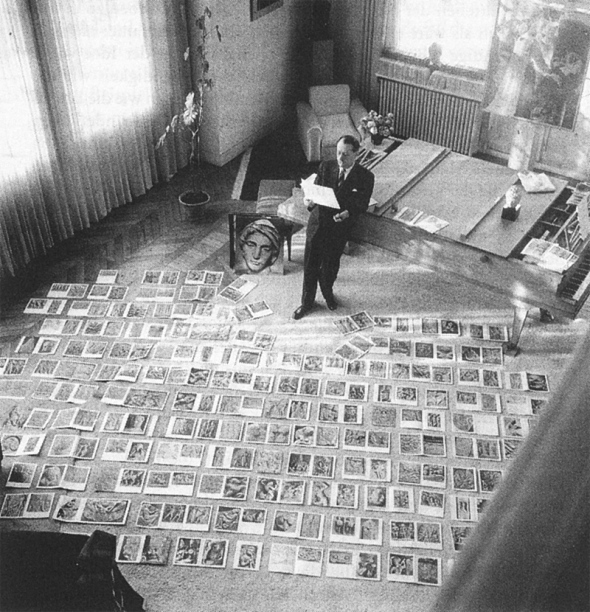

Malraux argues that his collection of reproductions performs the same transformative function but better. Photographs or art are not bound by the limitations of physical display. Exhibiting pictures of artworks is infinitely easier to access/transport/display/juxtapose than the artworks themselves. In an instant, one can place a picture of The Sphinx beside a picture of the Eiffel Tower.

True! However, what Malraux failed to anticipate and what his supporters fail to take into account is that our society has, in the decades since the book was written, fundamentally changed the way we interact with images. The great flattening of scale and texture and mobility that Malraux championed in his museum of photographic reproductions means, in the age of Facebook and Pinterest, that a picture of a Rubens painting has the same viewing impact as a picture of my neighbor’s cat.

The thing about walls is that they separate. They are a means of organization, a platform upon which objects cohere into greater meaning. Museums were able to transform objects into art by setting them apart from everyday life in a special place so that the viewer was physically, visually, mentally primed to experience the exhibition in a certain way. In the digital sphere, Malraux’s Museum Without Walls is a museum without the mental space for contemplation as art. Online, the aura of the object-transformed-into-art is lost in the infinite sea of images.

How to create an image-based online exhibition with “walls”– an exhibition that creates this mental environment? Stay tuned for Part 2!

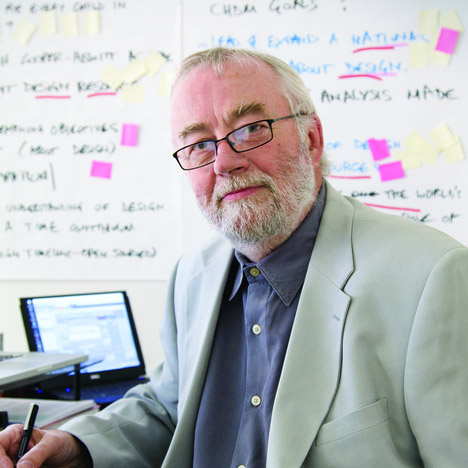

Remembering Bill Moggridge, Designer and Museum Director

Posted: September 10, 2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Bill Moggridge, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum 1 CommentBill Moggridge, Founder of the design firm IDEO, designer of the first laptop computer, and Director of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, passed away on Saturday at the age of 69.

Moggridge is undeniably one of the great design luminaries of our time. I didn’t know that he was ill but given the prompt appearance of a comprehensive and well produced memorial on the Cooper-Hewitt’s site– http://www.cooperhewitt.org/ — it can’t have been a surprise.

I only met him once, after a lecture he gave at the Design Criticism program in November of 2010. It was a canned talk about the Cooper-Hewitt, little more than a PowerPoint museum brochure, really. Afterwards, at the reception, I was simultaneously irked by his lecture and awed by his stardom. I’m ashamed to admit that I totally bungled our brief interaction. I rather bluntly asked him if the Cooper-Hewitt had guns in its collection (I’d only just begun my research into that topic which eventually turned into my thesis). Moggridge, standing near the bar and holding his little plastic cup of red wine, was clearly uninterested, replied that he didn’t know if the Cooper-Hewitt had guns and turned away dismissively.

And that was that.

Can’t blame the guy. I knew that they didn’t have guns but I wanted him to tell me that they didn’t and why. I know now, after having gotten a little practice in the fine art of getting important people to divulge their secrets, that my opener should have been more of a tease than a confrontation. I blew it. And now I’ll never have the chance to get inside his head.

In my mind, it’s like there were two Bill Moggridges: the charismatic, genius designer and design thinker who created iconic products and got Michelle Obama to back the National Design Awards and then the mildly bored old man who didn’t feel like indulging the provocations of an uninformed wanna-be design critic.

Oddly Delightful Museum Opens In Former Gitmo Detention Center

Posted: September 9, 2012 Filed under: Museum News | Tags: Gitmo, Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History 2 CommentsFiction reveals truth that reality obscures. — Ralph Waldo Emerson

On August 29th, the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History officially opened its doors in the former US detention center in southeastern Cuba. Dedicated to remembering the infamous prison, the museum features exhibitions of conceptual artwork in addition to essays created through its critical studies center.

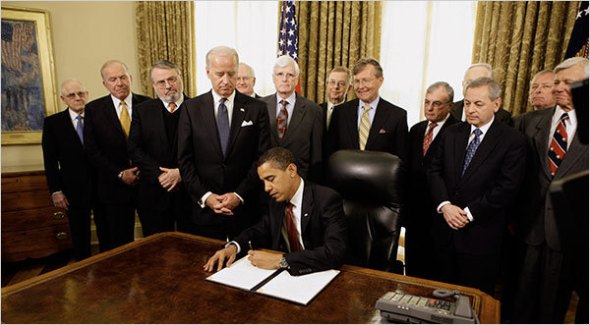

Well, sort of. The Gitmo Museum is a critical fiction of sorts, an attempt to reach truth by coming at it obliquely but thoughtfully. Although Barak Obama officially signed legislation that would shut down the detention center in Guantanamo Bay in 2009, it’s still open. In a Senate hearing in January of 2011, Defense Secretary Robert Gates said, “The prospects for closing Guantanamo as best I can tell are very, very low given very broad opposition to doing that here in the Congress.”

The outrage prompted by initial coverage of the human rights abuses in Gitmo has died down in the ensuing years and tide of bureaucratic complexity. But this team of artists and thinkers is using a creative fiction to cheekily re-open the conversation.

There is an undeniable psychological power associated with place, a sense of connection across time. The Gitmo Museum’s brilliant digital appropriation of physical space, though a fiction, plays off of this power of proximity. The site generates a greater emotional impact by giving the impression that these artworks inhabit the same physical space as the atrocities they address. The subject matter is unabashedly serious and dark but its presentation and fictional container render the overall effect oddly delightful.

Learn more about the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History (and plan your visit?) here: http://www.guantanamobaymuseum.org/

Experiential Exhibition: The Simulated Bomb Shelter

Posted: March 27, 2012 Filed under: Event, Museum News | Tags: Artists 4 Israel, Columbia University, experiential exhibition, Israeli Bomb Shelter Museum, Paul Virilio, Simulation, War and Cinema Leave a commentAccording to metro,the pro-Israel graffiti group Artists 4 Israel was recently turned away from Columbia University where it intended to bring a controversial Israeli Bomb Shelter Museum. The “museum,” housed in a replica bunker similar to those found in Southern Israel, simulates the experience of a rocket attack through the use of sound and video. The group set up the museum last year in Washington Square Park but the loud noise quickly drew police attention and it was closed down after just half an hour.

The Artists 4 Israel website has recently been hacked but Israeli National News quotes a description of the project:

“The bomb shelter is a Museum of Living History and Art Installation. A functional bomb shelter built in the exact specifications of those found in Sderot, Israel, on the border of Gaza, this refuge mimics the feel, look, small and sounds of the original. From wailing ‘Red Alert’ sirens to interactive computer terminals, a multi-media presentation provides facts and education about the conflict in the Middle East while artistic flourishes create emotive and important and visceral reactions in the visitor.”

The description of this proposed exhibition made me feel a little squeamish. Not only because of the sometimes anti-Palestinian vibe of the artists but because the projects reminded me of something Paul Virilio wrote about in his startling book War and Cinema:

“After 1945, this cinematic artifice of the war machine spread once more into new forms of spectacle. War museums opened all over liberated France at the sites of various landings and battles, many of them in old forts or bunkers. The first rooms usually exhibited relics of the last military-industrial conflict (outdated equipment, old uniforms and medals, yellowing photographs), while others had collections of military documents or screenings of period newsreels. It was not long, however, before the invariably large number of visitors were shown into huge, windowless rooms resembling a planetarium or a flight (or driving) simulator. In these war simulators, the public was supposed to feel like spectators-survivors of the recent battlefield.

…

If one thinks of the cinema-mausoleums or atmospheric cinemas of the thirties, one can see in this a new outflanking of immediate reality by the cinematic paramnesia of the war machine.

…

The sites chosen for museums of the Second World War remind us that these fortress-tombs, dungeons and bunkers are first and foremost camerae obscurae, that their hollowed windows, narrow apertures and loopholes are designed to light up the outside while leaving the inside in semi-darkness.”

(pg 48-49)

Art often appeals to the emotions of the viewer but there is always a risk when mixing reality (such as the complexities of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) with fantasy.

On the other hand, aren’t all museums places of fantasy to some degree? They’re constructed environments, representations of the past or emissaries from an idealized present/future. The difficulty is creating some kind of truth through the narratives told and the objects/experiences used to tell them, the transformation of a kind of fiction into reality. But according to Virilio, it goes both ways; if I found myself in an actual war zone, I’d likely feel that I was in a movie. Fictionalizing reality through simulation can provide access to events but does it also train us to experience the world as no more than representation?

Smithsonian’s Video Game Exhibition

Posted: March 22, 2012 Filed under: Event | Tags: Art of Video Games, Call of Duty, Chris Melissinos, Exhibition, Flower, Grand Theft Auto, MassEffect 2, Pitfall, Skyrim, Smithsonian, trailer 1 CommentI WANT TO GO SO BADLY!

How To Not Make A Museum

Posted: March 21, 2012 Filed under: Museum News | Tags: Economic Development Corporation, Edward Hopper, Lighthouse at two lights, National Lighthouse Museum, Staten Island Leave a comment

The Lighthouse at Two Lights by Edward Hopper (at The Met)

http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/210009492

I’m a freak for lighthouses– maybe it’s because of the trip to a couple of North Carolina lighthouses when I was a kid or from watching one too many episodes of The Road to Avonlea. Regardless, when I heard that there was a National Lighthouse Museum located just over the harbor in Staten Island, I was ecstatic! That is, until I did a little Googling.

Turns out that although an SI organization won the title “National Lighthouse Museum” in 1998, there’s still no museum. According to Staten Island Live:

The problem is that no one has come up with the funding required to transform the 19th century buildings on the site into a museum. Everybody seems to have been waiting around for somebody else to do the heavy lifting. It was as if everyone thought merely getting the designation was enough.

The city’s Economic Development Corp., which has always seemed a reluctant partner in this enterprise, did put about $8 million into stabilizing the buildings and constructing a first-rate new pier. But the EDC has maintained, with some reason, that the job of getting the museum up and running should fall to the museum’s backers, not city government.

The board of the museum never came close to raising the $15 million needed to get the museum going. Then, a couple of years ago, the board formally dissolved in what seemed to be the death knell for the museum.

But apparently there is a new board for the organization and renewed efforts to raise the several million dollars required to turn the proposed museum into a reality. Let’s hope they do right by it and ward off the muggers. Exploring a museum dedicated to lighthouses sounds like it would be a wonderful way to spend a spring afternoon.

Children + Chessmen at NY Museum

Posted: March 19, 2012 Filed under: Event, Museum News | Tags: Aisle of Lewis, chess, Chessmen, children, Harry Potter, medieval art, museum outreach, religious art, The Cloisters, wizard, Wizard's Chess Leave a commentI spotted this gem in The Wall Street Journal’s New York Photos of the Week March 10th–March 16th with the caption:

About 30 public elementary school children compete in a chess tournament sponsored by Chess-in-the-Schools at The Cloisters Museum in New York on Sunday, March 11, 2012. The museum is currently displaying an exhibition “The Game of Kings: Medieval Ivory Chessmen from the Isle of Lewis.”

I hadn’t heard about the chess exhibition at The Cloisters but as a former high school chess geek, I know that the medieval Lewis Chessmen are some of the most famous historical game pieces (not to mention that Ron and Harry used them to play Wizard’s Chess in the first Harry Potter movie).

The pieces are thought to have been made in Norway and were probably abandoned on the Aisle of Lewis (which is near the west coast of Scotland) by a 12th century merchant. The pieces were lost until 1831 when they were unearthed with a whole trove of other objects. From the Met’s website:

The chess pieces (thereafter known as the Lewis Chessmen), which come from at least four distinct but incomplete sets, are today arguably the most famous chess pieces in the world, and are among the icons of the collections of the British Museum in London and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

The King below is obviously aghast that I haven’t visited him already.

(image via the Met’s website)

(image via the Met’s website)